Nobody Ever Asked You to Write

Said the writer Raymond Carver to my friend Martha. Plus: questions of containment and fine new books by Chris LaTray, Martha Gies and Arron Magar

Truth & Dare is a monthly post that offers one Truth (a writing prompt) and one Dare (an artistic gesture in the world). You might also find: thoughts on writing, art, books and paying attention. You won’t find: a paywall or a thicket of hyperlinks taking you someplace else. Just a clean read, a cup of herbal tea poured over your frontal lobe. No noise. No distraction. Thanks for being here.

Also: I’ll be teaching an in-person Memoir class at The Attic1 - Six Mondays: 10/14-11/18 in Portland, 10-11:30. Generative, convivial, fun. Come join us!

Recently I read at a faculty reading for the Atheneum2, from pages I’d grabbed at the last minute, after changing my mind about what to share - kind of like a literary version of hastily switching outfits and running to stand in front of a mirror before leaving the house. Afterward, my friend Brian told me he’d liked it, and said, “I know you’ve worked on this for a while now - how close do you think you are to being finished?” In that moment, the perfect metaphor came to me. “It’s like a wildfire,” I told him, but it’s only about 2% contained.”

Something burning out of control feels like a good description, though it’s less on fire (at least for now) than it is just..uncontained. For one thing, it’s a real shape-shifter of a project. It’s been a novel, then a novel in a drawer, (sidelined by the arrival of babies), then a novel in a drawer (sidelined by an art project that turned into a nonprofit3 that turned into a book4), and finally a nonfiction hybrid version told in weird scripture. It’s even embedded here and there throughout a sprawling document I named Novel Ways to Sneak Up on a Novel, pages I wrote over the years to get around the impediment of myself, a place I went to bellyache about not writing, (currently at 750 pages, which may challenge the veracity of my bellyache). So yeah, for now it’s unwieldy, but I trust the story there and believe that if I keep showing up for it, there’s a way to contain it and settle it into the form it wants to be.

The writer Martha Gies has an essay in her new collection about studying with the great Raymond Carver, before he was as famous as he’d eventually be. There’s a sweet line about how he conducted their workshop:

If someone asked a jokey question he never responded in-kind. He always answered carefully as if understanding that jokes often come from nervousness or self-consciousness. If someone made an ironic, self-deprecating aside, or—God forbid—a cruel remark, he stared off quietly for a moment, often smoking, patiently waiting for us to recall ourselves to generosity.

Carver doesn’t spend too much time telling students how to get published, but he does share with them a banner moment when he received 2 acceptance letters on one day, one for a short story and the other a poem. When he tells the students he has been paid $1 for the poem, (it was 1960 at the time, back before poets were paid fabulously for their work), they can’t believe it.

“But then nobody asked you to write,” he tells them with a smile.

It’s true that nobody asks us to write. Maybe we write to gather and contain ourselves. We write to restore order to a disordered world. We write to locate some meaning and then share it with everybody else. We write to feel less lonesome. We write toward catharsis, revelation. We find a pulse and then we follow it to find its heart. Nobody asks us to, but we do it.5

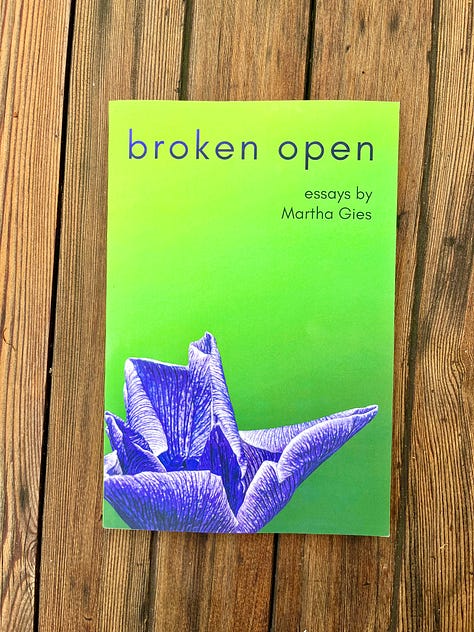

There are three new books in the world, and I was lucky to help in the editing stage with two of them. Martha Gies is a longtime teacher and writing mentor to many, including me. That’s why it was an honor (and mildly terrifying) when she asked me to read and give feedback on her manuscript. The book Broken Open is out now, a memoir-in-essays from Trail to Table Press6, and it is exquisite. Martha’s keen eye for detail is evident in the portraits she writes of the characters from her life, (a man on Skid Row, a Portland Black Panther, her own sister, dying of cancer) but what I especially love about this book is the ways she has finally turned that lens on herself. I write about this in a review for Street Roots newspaper.7

I met Arron Magar at Columbia River Correctional Facility in a writing workshop and that first day, he read to us about being driven as a kid to yet another foster placement in his stocking feet, so he wouldn’t run away. Like the others in the workshop, Arron was dealt a difficult hand from the time he was young. What he makes of this, the meaning he draws, and the clear, distinct voice in which he tells it, becomes a powerful account of survival. As I wrote in the forward to the book, he “explores themes of brotherhood, displacement, addiction, and lonesomeness. Arron can write bleakness like Charles Dickens and his keen observations of living at the margins of a city, surrounded by the rhythms of the outdoors, makes for a riveting narrative.” Since his release (weird, I first typed relief) Arron has balanced promoting his book with work and family life. He’s also documented visits to some of his old haunts in the city.8

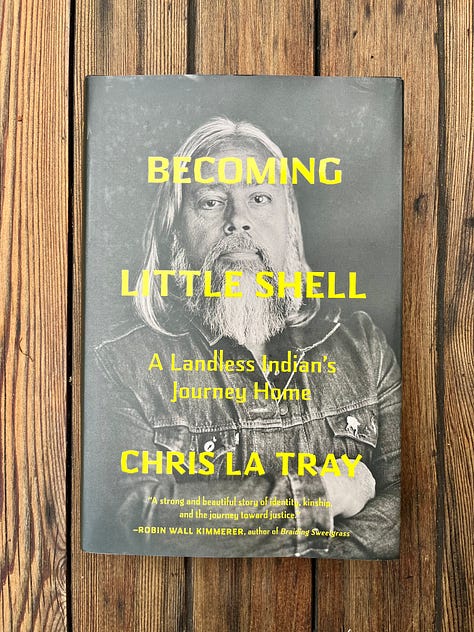

Chris LaTray’s work came onto my radar during the pandemic in the form of his newsletter, An Irritable Métis9. At turns tender, furious, rapt, and poetic, it was seriously one of the things that kept me upright during sideways times. His book, One Sentence Journal: Short Poems & Essays From the World At Large, is full of potent sentences that observe a scene from life and then distill it into a sentence that even Basho would be proud of. Here’s the first one he ever wrote: “07/01/2013: I found myself in the company of James Lee Burke while waiting for a tire repair at Les Schwab…” He writes about birds and horses, bumper stickers and Montana, the place he calls home. The practice of the one-sentence journal, a daily line that captures a moment, feels both low-bar (easier when there’s not a whole blank page to fill) and freighted with potential, as the sentences accumulate. His new book, Becoming Little Shell: A Landless Indian’s Journey Home, explores the indigenous heritage that his father always denied, but LaTray claimed — it takes going to his grandfather’s funeral and looking around at the many native people there to affirm his sense of identity and to spark new questions about his family history. LaTray embarks “on a journey into his family’s past, discovering along the way a larger story of the complicated history of Indigenous communities—as well as the devastating effects of colonialism that continue to ripple through surviving generations,” (from Milkweed).

I got to see him in a stellar conversation with writer Sierra Crane Murdoch, (author of Yellow Bird: Oil, Murder and a Woman’s Search for Justice in Indian Country10) at Powells last week, and it was an excellent, wide-ranging discussion, (in my notebook I wrote: “Chris read J.R.R. Tolkien, Conan stories and the Chronicles of Narnia,” and “Even the way we define tribal affiliation comes from colonialism”). Can’t wait to read his book!

And now it’s time for this month’s Truth & Dare:

Truth: With thanks to Chris LaTray, in the style of One Sentence Journal, write the date and then a single line that captures a moment from your day. Bonus points if you do it daily for a week or more, to see how the sentences begin to form sedimentary layers, (share with us in the comments!)

Dare: Challenge a friend to do the One Sentence a Day practice with you for a full week, and share your sentence with them each day, (a photo texted by phone counts). Bonus points if you send someone your sentence on a postcard in the postal mail. Triple Dog Bonus if you send a postcard with a sentence to me.11

That’s it for this month. If you’ve read this far you’re either my auntie or the best reader I could have hoped for, (One and the same? Love you, Aunt Nancy). Reader, I’m grateful to you on this drenched and dark rainy Portland evening, and I’m sending you courage and fortitude and love and familial feelings and just now I went out onto the wet grass, and I blew you a kiss.

Not gonna lie, I had to listen to the pronunciation guide several times before I felt like I could accept the offer to join the faculty

Loaners: The Making of a Street Library, now in its second print run, with an audiobook recorded and due out in November (!)

The third or fourth time I read this paragraph through, it began to set off a Malarkey Alarm so if it did that for you, it’s okay. And if you liked it, thank you.

See that here and buy his book here — cover art is by the rad artist Chris Johanson

Laura Moulton, PO Box 13642 Portland, OR. 97213

I sure loved seeing you, Laura!